The Corporate Governance Code as a Tool for Sustainability

Where do we come from and were are we going?

Introduction

The introduction of the notion of ‘sustainable value creation’ in the Belgian Corporate Governance Code (so-called 2020 Code) is considered as an innovative change. It mirrors the evolution in the ‘zeitgeist’, in which sustainability is on top of the agenda. It also marks the intention of the Corporate Governance Commission to set the tone and stimulate companies to engage in a substantial transition. Is the 2020 Code in line with other national codes or rather the exception? Can the Code be an effective tool for sustainability?

Interesting questions that trigger GUBERNA to delve into the literature in order to be able to position the 2020 Code in an historical and international context. Moreover, insights are provided to stimulate the reflection whether the 2020 Code is in need of an update.

Origin of Corporate Governance Codes

The first code of good governance was issued in the US in 1978, in the wake of a series of notable mergers and hostile takeovers. Hong Kong and Ireland followed in 1989 and 1991. In Europe, the development of national corporate governance codes accelerated after the publication of the 1992 Cadbury Committee Report: Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance in the UK; well-known as the “Cadbury Code”. This report responded to an increased public concern about the unexpected collapse of some major British Companies and soon became the flagship guideline. Many other countries got inspired by the Cadbury Code and used it as a source of inspiration.

The creation of national corporate governance codes worldwide was further stimulated by the occurrence of corporate malpractices and crises as well as by the issuance of influential transnational codes such as the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance in 2004.

The traditional codes on corporate governance are developed for listed companies but throughout the years there is a proliferation of codes aimed at improving the governance of other types of companies (e.g. non-listed, social profit etc.).

Interesting fact: By the end of 1999, at least one corporate governance code was published in 24 countries resulting in total of 72 codes. By the end of 2014, in 91 countries a code and/or a revised code was issued, resulting in a total of 345 codes (91 first codes and 254 revisions).

A Corporate Governance Code is commonly described as a set of best practice recommendations regarding the structure, role and functioning of the governance bodies - in particular the board of directors - of a company. The objectives of the first generation codes, developed for listed companies, were clearly described : (1) improving the quality of the governance of a company and (2) increasing the accountability of companies to shareholders.

In fact, the rationale of many national corporate governance codes is rooted in a shareholder-oriented view, or put differently in a principal-agent view. In this view, conflicts of interest might occur between the managers (agents) and the owners/shareholders (principal) of a company. The issue at stake is how to assure that the managers behave and decide in a way that contributes to optimizing the return on the investments by the owners/investors. In this respect, Codes were designed to address governance deficiencies, in particular regarding the protection of (minority) shareholders. They are considered of utmost important when other mechanisms such as the takeover markets and the legal environment fail to safeguard shareholder rights.

Additionally, it must be noted that the issuers of codes vary among the countries and even within a country. They include stock markets and/or its regulators, investor associations, business associations, directors’ associations, … and even government. The importance of understanding who the issuers of a code are may not be underestimated as it provides critical information on the national context of the Code, its content and its enforcement (see infra).

The rapid spread of corporate governance codes has also triggered academic research on this topic. Of particular interest is the influential work done by Ruth Aguilera and Alvaro Cuervo-Cazurra. They studied the determinants of the diffusion of corporate governance codes across countries and provided evidence that both domestic forces (or efficiency reasons) and external forces (or legitimacy reasons) explain the adoption of codes. External forces refer to the pressure following opening up of financial markets, the presence of foreign institutional investors, globalization of the economies etc. In this respect, a code has the ability to introduce international accepted practice in a country’s corporate governance system in order to enhance its legitimacy in the global economy. Domestic forces refer to the demand of (local) investors to better protect their interest and holding managers and directors accountable. A code is considered a rapid way to fill gaps in the legal system and as such increases the efficiency of a country’s corporate governance system.

Evolution of the Belgian Corporate Governance Codes

The first Belgian governance initiatives dated back to 1997. Separately, but in parallel, the Federation of Enterprises in Belgium (VBO/FEB), the (former) Banking and Finance Commission and the Brussels Stock Exchange published a set of recommendations on corporate governance. The format and content of the three initiatives were different but complementary and purely voluntary in their nature. Unlike other countries, Belgium did not have any high-profile accidents or scandals that were the immediate trigger for the development of the codes at that time, although one argues that the discussions on the role of reference shareholders, following high profile cases such as Wagons Lit and Tractebel-Electrabel have undoubtfully contributed to this. Moreover, partly in the light of the introduction of the Euro, awareness grew that capital markets would lose their national identity and strong competition for financial resources would emerge. Belgium wanted to strengthen the competitiveness of its companies on the international scene by improving transparency to shareholders and potential investors, in particular on the quality of the governance. The three “codes of conduct” were all three inspired by the recommendations of the Cadbury Code, in order to align with internationally accepted standards. Yet, none of them were in favour of a simple “copy-paste”. They intentionally wanted to take into account the specific Belgian situation where listed companies are characterised by concentrated shareholders. The issue at stake here is the dominant position of one or more reference shareholders, described in the literature as an agency problem between controlling and minority shareholders.

In 2004 the three initiators joined forces and established the Corporate Governance Committee to draft a single code of best practices. This followed a series of legal interventions by the European Commission since the launch in 2003 of its Action Plan on ‘Modernising Company Law and Enhancing Corporate Governance in the European Union’ (see infra). At the end of 2004, the first joint code was born (so called “Lippens Code”, named after the Chair of the Committee).

The Committee's main objective is to ensure that the Belgian Corporate Governance Code's provisions remain relevant to listed companies and are regularly updated in line with practice, legislation and international standards. In 2009 and 2019 the Code was revised.

The implementation and enforcement of Corporate Governance Codes

The introduction of corporate governance codes and guidelines also gives rise to questions about their implementation, effectiveness and enforcement. Obviously the level of enforceability of a Code is closely linked to the identity of the issuer of the Code. The initial guidelines by the former Banking and Finance Commission in Belgium for example were based on a pure publicity system (“disclosure”), requiring minimum information relating to certain aspects of corporate governance to be disclosed in the annual report. The Hong Kong Code, issued by the Stock Exchange, was of a different kind and compulsory for listed companies to adhere to its provisions. Moreover, the legal environment within corporate governance codes functions adds another level of complexity and differentiation.

More detailed analyses by well-respected law professors have revealed that across countries and in particular across jurisdictions, different enforcement mechanisms can be identified: ranging from “voluntary” to “mandatory” or a combination.

Voluntary mechanisms include codes which have the status of mere recommendations which are not legally binding. The implementation is voluntary and based on self-proclamation. One relies on the assessment by market forces for its enforcement. At the other end of the spectrum, mandatory mechanisms refer to detailed corporate governance provisions laid down in law.

Mechanisms that combine both options are for example a code that is part of a stock exchange listing requirements. Another example is when the law explicitly refers to a corporate governance code.

For decades, most people were averse to the development of stringent corporate legislation (so called “hard law”). As such a compulsory approach was rarely found in codes of good governance. A well-known exception was the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) enacted after several accounting scandals in the US. The approach that generated by far the most support was self-regulation, linked to openness and flexibility as well as the reliance on the capital market to monitor and assess the value of compliance. This so-called “soft law” approach is commonly based on the “comply or explain” principle. Companies are excepted to comply with the recommendations of the Code but in cases of non-compliance they must explain the reasons for the deviation. A variant is the “apply or/and explain” regime which shows an appreciation for the fact that it is often not a case of whether to comply or not, but rather to consider how the principles and recommendations can be applied. In this view, the board could decide to apply the recommendation differently or apply another practice and still achieve the objective of the overarching corporate governance principles.

During the years, one has also observed an evolution in ‘the comply or explain’ approach. As Codes get revised, the more prescriptive and stringent the requirements become, denoting a shift from rather informal towards formal self-regulation. Moreover, practice has shown that the markets and investors fail in their role as effective monitoring mechanisms. Not surprisingly, the increased criticism on self-regulatory instruments have trigged the debate on the need for regulation of corporate governance and is still much alive today. (see infra)

As academic research mirrors business developments, a stream of empirical studies has emerged investigating compliance statements at national level, explanations for deviations from a corporate governance code as well as the relationship between code compliance and firm performance. They have enhanced the insights on the effectiveness and challenges of corporate governance codes.

Positioning the Belgian Corporate Governance Code(s)

All three Belgian Corporate Governance Codes (2004, 2009, 2019) are based on the comply or explain principle promoting a high degree of built-in flexibility, enabling companies to adapt the recommendations to their varying size, activities and culture. The 2009 and later on the 2020 Code got a legal recognition by means of a Royal Decree designating them as the reference code, respectively, for Belgium.

The Belgian Corporate Governance Committee stresses the fact that the 2020 Code is increasingly based on principles rather than on numerous detailed guidelines and rules. It also recognizes that human behaviour determines company’s long term success, and not all can be understood or regulated by principles.

Belgian listed companies need to report annually in their corporate governance statement to what extent they have followed the Code and if they do not, they are invited to explain why they have chosen to deviate from some of the provisions of the Code.

GUBERNA and VBO/FEB are entrusted to evaluate the implementation of the Code by means of recurrent studies (so-called “Monitoring Studies”).In the latest study, findings reveal that companies simply apply 89.9% of the provisions of the Code and for 6.4% of the provisions they explain why they deviate from them. This observation indicates that listed companies make little use of the flexibility offered by the "comply or explain” principle, as compliance rate with the Code is very high. In addition, there is still room for improvement regarding the quality of the explains provided. The Belgian Corporate Governance Committee closely follows up on the findings and takes several initiatives to enhance awareness and support listed companies in the implementation of the Code.

Convergence or divergence of Corporate Governance Codes (and their contents)

Discussions on corporate governance codes are strongly linked with the critical debate on the convergence or divergence of corporate governance systems and practices. Initially the assumption of convergence to the Anglo-American model was strongly advocated and arguments for this development are well documented. In contrast, many authors counter the idea of the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon model and argue that each national governance model is embedded in its cultural, historical, legal and social environment so that it forms a ‘system’ in itself. Large difference between resilient legal, political and institutional elements as well as the coupling of corporate governance with regulatory traditions in the areas of banking, labour, tax and competition law implies diversity in corporate governance model and hampers any converging initiative.

Empirical studies have been investigating the convergence-divergence hypotheses in relation to corporate governance codes. Findings mainly point to the fact that divergence prevails around the world and that the content of codes does not reflect a strong convergence toward the Anglo-American governance model.

Nevertheless, one could observe convergence in some governance practices across countries, enabled by similar provisions in national or corporate governance codes. The presence of independent directors, board committees, etc., are salient examples in this respect.

A next generation of research studies the impact of important transnational codes (such as the OECD Code) on the development of national corporate governance codes. The limited empirical evidence, so far, shows that some key recommendations advanced by these influential codes are being incorporated at the national level.

Of particular interest are the developments within Europe since the launch of the first action plan by the European Commission in 2003 (see infra). The question arises to what extent the national corporate governance codes reflect the recommendations issued by the European Commission. One of the first studies in this respect has revealed that codes of Eastern European Countries cover on average 50% of the recommendations of the European Commission suggesting that domestic forces related to country-specific characteristics are still influential in shaping the content of the codes. A follow-up study enlarging the scope to 27 members states of the European Union shows a high level of compliance across the national codes as well as a strengthening of codes quality over time although no robust evidence was found that these codes were directly influenced by the EC recommendations.

Corporate Governance Codes at the heart of the CSR/stakeholder and sustainability debate

Given the fact that corporate governance codes reflect differences in corporate governance models, one cannot ignore the view on the role of stakeholders. The shareholder-stakeholder dichotomy traditionally forms the fault line between the two prominent governance models and is still the topic of discussion today. Countries with an Anglo-Saxon legal tradition prefer a shareholder-centric governance model ('outsider' model) while countries with a German, Scandinavian or French legal tradition are characterised as stakeholder-centric ('insider' or Rhineland model).

Moreover, the importance of stakeholders is recognized in the development of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the underlying stakeholder theory. The two disciplines – corporate governance and corporate social responsibility – have quite different roots and objectives, but have developed along similar paths and are increasingly becoming linked. Originally corporate governance and the codes were directed at the internal workings of the company (= dynamic between shareholders, board, managers and employees) and perceived as an instrument to enhance and protect shareholder value. The UK and US are considered as the bastion in shareholder primacy. The objectives of CSR, on the other hand, are more diverse (beyond shareholder value maximalisation) and take into account how the company affects the wider society (beyond internal company affairs). Nevertheless, one argues that corporate governance and CSR share many common features that are likely to promote good corporate governance and at the same time encourage better CSR.

The seminal study by Szabó and Sorensen in 2011 has investigated the role of corporate governance codes in in promoting environmental and social responsibility. In particular they analysed to what extent and how national corporate governance codes in 30 European countries addressed stakeholder issues as well as social responsibility and ethical issues. The authors concluded that corporate governance codes already included recommendations on stakeholders and core CSR issues, but they were quite generic, vague, mainly related to transparency and subordinated to the shareholder primacy principle.

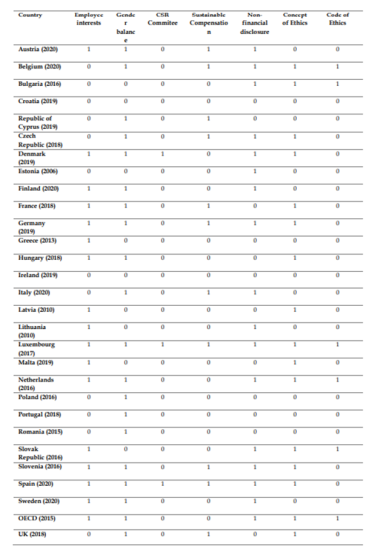

A follow up study in 2020 by Siri and Zhu analysed the content of corporate governance codes in force in all 27 EU Members states. In fact, they mapped to what extent CSR and/or sustainability issues are referred to in the Codes based on the following criteria :

-

The purpose of the code and of corporate governance

-

CSR/sustainability

-

Stakeholders

-

Employees

-

Gender diversity

-

Sustainability/CSR committee

-

Compensation and sustainability

-

Non-financial disclosure

-

Ethics

Overall, they noticed that a growing number of codes tend to mention sustainability issues, signalling a growing interest in this matter. Nevertheless, they still identified gaps and weaknesses for each criteria. Moreover they argue that further effort is needed to fully integrate environmental and social issues in corporate governance codes as the shareholder primacy rule is far from being overcome. Put differently, sustainability issues, and in particular stakeholders’ interest’, are considered to the extent to which they could impact shareholder value. They expressed hope towards the upcoming new EU legislation on mandatory human rights and environmental corporate due diligence and other initiatives with respect to sustainable governance to stimulate a more homogenous, complete and coherent approach towards sustainability issues in the Codes.

In fact, these studies are in line with the well-known work of Sjäfjell, which showcases – from a legal perspective - the failure of corporate governance codes to support CSR objectives.

Positioning the Belgian Corporate Governance Code

The study by Siri and Zhu also included the Belgian Corporate Governance Code (2020 Code). In their analysis the 2020 Code scores quite well on the criteria they have investigated (see attach). However, they observe room for improvement with respect to (1) the definition of corporate governance and stakeholders, (2) specific recommendations in relation to employee rights/interests and (3) the introduction of a CSR Committee.

Meanwhile a few Codes, in particular the Dutch, French and German Code have been revised. A preliminary cross country analysis by GUBERNA reveals the continued rising interest for sustainability issues. In particular, the new versions of the Codes stress the need for long term/sustainable value creation, refer in a consistent way to social and environmental factors and recognize stakeholder interests. This is still in line with previous observations.

In addition, the revised Codes are becoming more advanced on specific sustainability-related matters by explicitly including provisions on culture (e.g. Dutch Code), required expertise and training of board members (e.g. German and French Code) and by specifying ‘climate’ (e.g. French Code).

Finally, the notion of diversity is broadened as it is no longer limited to gender while reference is also made to anti-discriminatory practices (e.g. French Code) and inclusion (e.g. Dutch Code).

The future of Corporate Governance Codes: co-existence of hard and soft law?

The debate about the effectiveness of both hard and soft law mechanisms in promoting corporate governance, -and parallel CSR - , is not new.

For a long time, the European Commission did not opt for hard law interventions in corporate governance nor CSR. The improvement of corporate governance standards was mainly addressed by means of soft law mechanisms - such as the promotion of corporate governance codes and recommendations - with the exception for the financial sector.

Nevertheless, hard law lurked around the corner. Noteworthy are the three Green Papers describing the evolution in the rationale regarding future regulatory initiatives, resulting in concrete EU directives as disclosed in the Corporate Governance Action Plan 2012.

As to sustainability, the interest of the European Commission dated back to 2001 with the launch of the EU Sustainable Development Strategy and has been strengthened by additional commitments. The first EU legislative interventions to promote corporate sustainability has developed along two main intertwined dimensions: sustainable finance and corporate non-financial disclosure. More recently, the proposal for a Directive on corporate sustainability due diligence announces a new, far reaching step in this trajectory. It is considered as a real game-changer in the way companies operate their business activities throughout their global supply chain.

The Directive was preceded by a number of studies, among them a “Study on directors’ duties and sustainable corporate governance”. This study also analyses various options in EU level approaches ranging from voluntary measures to the adoption of legislative measures. The study was strongly criticized while also the Directive is not without controversy.

Given the evolution towards hard law, the question arises what role Codes could still play in fostering a transition towards a more sustainable economy and business. A debate that is also prevalent in academic circles, at first in anticipation of the decisions of the European Commission, and later sparked by a provoking paper issued by Cheffins and Reddy, entitled ‘Thirty Years and Done – Time to Abolish the UK Corporate Governance Code’. Arguments pro and con are well documented and mirror the different perspectives.

We flag out some elements to encourage the reflection regarding the future of the Belgian national codes:

-

A common trigger to review a code are new developments, not in the least as a response to corporate malpractices or alignment with an evolving regulatory context. What is/will be the rationale to (further) include sustainability issues in national corporate governance codes? Moreover, how can de Code avoid duplication with requirements includes elsewhere and refrain from including vague platitudes which reflect corporate common sense? This rather critical question is in fact stressing the need for (more) qualitative provisions supporting sustainability.

-

It is argued that codes might be seen as a ‘softer’ option to the legislator to signal a renewed approach to corporate governance and a deviation from the path dependence shareholder primacy norm. Can a Code live up to this expectation? Does it change the initial objective of the Code?

-

In contrast, this ‘softer’ option is also being criticized as being a temptation for policy makers to duck hard policy choices with respect to challenging governance issues. The increasing governmental interconnection (in countries such as the UK) with the body in charge of drafting and updating the Code fuel this criticism. In contrast, in other countries one observe rather a vague interest of public authorities in shaping Codes. How is the Code perceived in a context of increased state involvement in business?

-

A recurring criticism is the ‘box ticking’ approach, as opting out of provisions on a comply-or-explain basis is not really embraced. It is argued that investors, proxy advisors and other interested parties (such as the FRC in the UK) expect substantial compliance with the Code, are unwilling to accept deviations and as such push companies to adhere to the Code. In some cases this implies an incorrect application of the Code and/or increased costs for those (smaller) companies for which some recommendations might be ill-suited. How can a national Code stimulate more flexibility and acceptance of the comply or explain principle in competing capital markets?

-

Overall, one often addresses the costs to companies of being subject to the Code. The requirements for companies listed on the stock exchange are increasing and “over-governance” is being cited a reason not to opt for an IPO or to delist. This evolution is not fostering the attractiveness of the stock market. To what extent is the Code perceived as a burden for companies seeking external capital?

The article by Tsagas provides interesting insights in favour of corporate governance codes supporting sustainable practices. She points out the relevant questions that should be tackled (see attach) and provide a clear proposal for reform of the corporate governance codes:

-

Provide a clear definition of the term ‘stakeholder’

-

Risk management should feature as a separate section

-

A separate section that focuses exclusively ensuring alternative forms of compliance with the Code (that go beyond the expected monitoring by the shareholders)

-

Monitoring function could also be exercised by bodies/agencies with expertise on issues relating to sustainability; consider alignment with information derived from the auditing of corporations on the sustainability practices

-

Remark: the author also recognizes the need for reliable sustainability metrics to facilitate (a) the market to ‘value’ sustainability, (2) the quality of the content of the monitoring of compliance and (3) assessment the utility of information that is disclosed.

Conclusion

Corporate Governance Codes have been around for more then 30 years and have had an important impact on business practices. Although they did not prevent malpractices – and will never to do – they are successful in raising the bar on ‘good’ governance at least for those companies that need to adhere to the Codes’ principles (first of all, listed companies).

Corporate Governance Codes have also shown their vulnerabilities and are not without criticism. For sure the comply or explain principle, a code hallmark, does not fully obtain its objective and the self-regulatory character is under pressure due to the rapid evolution of regulatory initiatives. However, abandoning the codes would be to “throw away the baby with the bath water”.

Corporate Governance Codes have already shown their dynamic nature by means of regular revisions, capturing new development. Currently, business and society are on a crossroad. They face many challenges not in the least with respect to environmental and social issues. Many parties take initiatives to stimulate and support companies in the required transition towards a green and more sustainable economy.

In this context, the role of corporate governance codes is also being discussed. One is aware that it is time for a change but the “right way to go” is not yet agreed upon. The reflection is ongoing and one need to keep in mind that the relationship between the content of a code and quality of information that is disclosed is a delicate one. Equally, stimulating improvement by incentives or by sanctions is a balancing act, as well as looking for a way to mobilizing and empowering the ‘right’ actors for the enforcement.

Remark : this publication is part of a series of studies related to sustainability. Next article will be based on a the firm-level study with respect to the implementation of the notion of ‘sustainable value creation’ as included in the 2020 Code. This study is commissioned by the Belgian Corporate Governance Commission

References

Aguilera, R. V., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2004). Codes of good governance worldwide: what is the trigger?. Organization studies, 25(3), 415-443.

Aguilera, R. V., & Cuervo‐Cazurra, A. (2009). Codes of good governance. Corporate governance: an international review, 17(3), 376-387.

Bebchuk, Lucian A. and Roe, Mark J., A Theory of Path Dependence in Corporate Ownership and Governance (October 1, 1999). Stanford Law Review, Vol. 52, pp. 127-170, 1999

Cheffins, Brian R. and Reddy, Bobby, Thirty Years and Done – Time to Abolish the UK Corporate Governance Code (June 9, 2022). European Corporate Governance Institute -Law Working Paper No. 654/2022, University of Cambridge Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 13/2023,

Cicon, James & Ferris, Stephen & Kammel, Armin & Noronha, Gregory. (2010). European Corporate Governance: A Thematic Analysis of National Codes of Governance. European Financial Management. 18.

Cuomo, F., Mallin, C., & Zattoni, A. (2016). Corporate governance codes: A review and research agenda. Corporate governance: an international review, 24(3), 222-241.

Kubicek, A., Stamfestova, P., & Strouhal, J. (2016). Cross-country analysis of corporate governance codes in the European Union. Economics & Sociology, 9(2), 319.

Hermes, N., Postma, T. J., & Zivkov, O. (2006). Corporate governance codes in the European Union: Are they driven by external or domestic forces?. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 2(4), 280-301.

Hermes, N., Postma, T. J., & Zivkov, O. (2007). Corporate governance codes and their contents: An analysis of Eastern European codes. Journal for East European Management Studies, 53-74.

Marchetti, Piergaetano and Passador, Maria Lucia, Thirty Years and Far from Being Done – Is It Truly Time to Abolish the UK Corporate Governance Code? (November 6, 2022). Bocconi Legal Studies Research Paper No. 4269661,

Siri, M., & Zhu, S. (2021). Integrating Sustainability in EU Corporate Governance Codes. Sustainable Finance in Europe: Corporate Governance, Financial Stability and Financial Markets, 175-224.

Szabó, D. G. (2013). Integrating corporate social responsibility in corporate governance codes in the EU. European Business Law Review, 24(6).

Sjåfjell, B. (2017). When the solution becomes the problem: The triple failure of corporate governance codes (pp. 23-55). Springer International Publishing.

Tsagas, G. (2020). A proposal for reform of EU member states’ corporate governance codes in support of sustainability. Sustainability, 12(10), 4328.

Wymeersch, E. (2006). The enforcement of corporate governance codes. Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 6(1), 113-138.

Appendix

Extract paper from Georgina Tsagas (2000)

The proposal for reform follows on from having considered the following key points when reviewing the sample of three Corporate Governance Codes:

(a) How are stakeholders defined in the Code?

(b) What type of information is required with regards to transparency? Who does the information target (the markets, the board, the stakeholders or the shareholders)?

(c) How powerful is the use of the words ‘should’, ‘could’ or ‘must’ when advising on any particular course of action and which is from a political or practical point of view preferable? Which section of the Code should this feature in? and

(d) To what extent should the Code advise on transparency regarding information on the company’s sustainability and impact on stakeholders, and on the engagement of stakeholders in the company’s corporate strategy or decision-making process?